Obamacare has quickly become a train wreck. Its troubled website, higher premiums, and inevitable shortages and rationing, married to President Barack Obama’s political refusals to enforce parts of the law, guarantee that the program will go down as one of the great public policy debacles in American history.

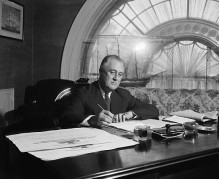

Unless the White House fixes the problems, the Obama legacy will be a government-controlled health care system that’s long on bureaucracy and short on doctors, with less treatment at higher cost. It is difficult to think of another domestic policy that failed so fast, for so many, at such expense. But one example from American history—Franklin Roosevelt’s rearmament program during World War II—provides both a warning and a guide. For while, as initially conceived, the national mobilization shared many of the fatal defects of Obamacare, changes were made in time to avert disaster, and the United States was transformed into the famous “arsenal of democracy.” Obamacare requires a similar course correction. Unlike the pragmatic FDR, however, today’s left so far refuses to reconsider and embrace market principles, preferring to sacrifice results on the altar of progressive ideology.

Committed to the belief that government is the solution to the nation’s most pressing problems, the Obama White House has not recognized that the real solution to the nation’s health care woes lies in less government, not more. The secret is to increase the supply side of the equation, instead of micromanaging the demand side, controlling what kind and how much coverage patients should receive, and eventually even how much treatment.

It is that lesson that Americans learned the last time Washington tried to take over large sections of the economy for its own purposes. In trying to get the United States ready for modern war—the U.S. Army was slightly bigger than Holland’s—Roosevelt was under intense pressure to direct the entire effort from the White House, placing the crash program under the control of a single all-powerful figure whose word would have the force of law. Harry Hopkins wrote in a secret memo that America had to “exceed the Nazis” in commandeering the economy. And in some areas, such as rationing and wage and price controls, the New Dealers got their top-down way, plunging the country into the kind of bureaucratic nightmare we see unfolding with Obamacare.

But in the all-important matter of converting a civilian economy to wartime production, Roosevelt had the sense to realize the job was too huge to be orchestrated by politicians and bureaucrats. Instead, he brought in top executives from industry to work out the timetable and means, using skills and experience developed in the marketplace. The result was the greatest industrial miracle of modern times.

Even so, when Roosevelt recruited business leaders like General Motors president Bill Knudsen, AT&T’s Bill Harrison, and U.S. Steel chairman Edward Stettinius to help him arm the country in the summer of 1940, they soon learned that his New Deal beliefs made their assignment harder, not easier. One was a deep suspicion of the profit motive. Roosevelt and his advisers instinctively assumed that letting companies make good money producing the warplanes and tanks and landing craft the nation needed was war profiteering. Knudsen and his colleagues in the Office of Production Management had to explain that the profit motive would actually incentivize America’s best businesses to commit time and energy and creativity to their task. “The more people we get” volunteering to go into wartime production, Knudsen told the president, “the more brains we can get into it, [and] the better chance it will succeed.” Obamacare’s rules are designed to do the opposite: to limit the number of insurance providers and types of policies on the market, and to discourage newcomers from getting into the field.

FDR’s second assumption was that certain strategic materials like rubber, steel, and aluminum were too vital to the war effort to be left to uncertain market forces and instead needed to be allocated by government in order to avoid shortages at critical points. But the opposite is true. Price controls and rationing plans, no matter how expertly designed, produce allocation distortions of their own—as the architects of Obamacare are about to find out.

The best wartime example was rubber. Roosevelt had decided that supplying enough rubber for the army’s vehicles required rationing the existing supply, including scrap rubber—at one point he even contemplated confiscating all the tires from civilian vehicles. Instead of hitting the minimum target of one million tons, the government’s rubber drive barely reached a third of that number. At one point the program’s director, Harold Ickes, was reduced to stealing rubber mats from the White House corridors.

The real way to secure strategic materials, Knudsen and his colleagues saw, wasn’t redistributing what was already available, but giving the private sector the incentive to produce more. As a result, companies banded together to create an entirely new synthetic rubber industry; companies working with new technologies like electric arc melting furnaces almost tripled prewar production of steel; and aluminum supplies, which in 1942 had been the despair of government planners, grew so fast thanks to new plants and new companies like Reynolds that just two years later an official confessed, “We have so much aluminum it’s beginning to run out of our ears.”

In fact, once Knudsen and Roosevelt’s other “dollar a year men” convinced the president and the Army to take a hands-off approach and let production build itself through the profit motive, they unleashed the most concentrated expansion of industrial production in U.S. history. War production saw a 300 percent increase from 1940 to 1944 and jumped from 2 percent of total economic output in 1940 to 40 percent in 1943—the climax of the wartime buildup—while raw materials like steel and copper saw an average 60 percent increase over the same period.

This despite the fact that war recruitment and the draft took almost 11 million able-bodied men out of the country’s labor force. But those numbers were more than made up by millions of people voluntarily leaving farms and rural areas and (in the case of women) their homes to find more lucrative work in the factories and shipyards of wartime America—all without a single government official telling them where to go.

By 1944, half of all war materiel produced in the world was coming out of American factories, plants, and shipyards. By this time, it was clear the Allies were going to win, and the problem was no longer speeding up war production, but slowing it down and then shutting it off at war’s end. What had come into being was precisely the kind of “spontaneous order” that free-market advocates celebrate but big government fans scoff at. As Colonel Orval Cook, production division head at Wright Field, summed it up: “Best results are secured . . . where there is a minimum of domination by the Army—and a maximum of flexibility for the private companies involved.”

Building the arsenal of democracy should have been a relatively easy task for government. Yet it wasn’t. A return to free-market principles was essential to get the job done with the necessary speed. Overhauling the health care system is harder, for several reasons.

For one thing, the government’s involvement in wartime mobilization is obviously constitutional. All agree that Washington has the power to manage the economy in order to successfully wage war. Obamacare’s constitutionality, by contrast, is contentious on multiple counts. Even a Supreme Court that upheld the Affordable Care Act in NFIB v. Sebelius recognized that Washington’s authority to “regulate commerce among the several states” did not allow it to impose mandatory, universal health insurance. The Court also agreed that Congress could not use its power to “promote the general welfare” to force states to expand their Medicaid programs against their wishes. It was only Chief Justice John Roberts’s implausible reading of the taxing power to permit penalizing individuals who don’t buy health insurance that saved Obama’s signature program.

And more constitutional defects are apparent. The Supreme Court has already accepted a challenge by corporations whose owners refuse to provide their employees health insurance that covers products and services to which they have religious objections. As the Obama administration continues improvising to stop the ACA from going under, it will make ever more extravagant demands upon the Constitution.

Second, even at the height of World War II, armaments, munitions, and military supplies still represented less than half of the goods and services the nation produced. Obamacare is more ambitious. It will eventually regulate the medical treatment of every man, woman, and child in the United States, not for a limited period of war, but forever. It goes beyond a wartime emphasis on the numbers of hard goods produced, such as munitions or airplanes, to permanently control services, where outcomes are more difficult to measure. It also seeks to replace the markets that aggregate the decisions of millions of people every day to allocate the economy’s resources. If the federal government couldn’t successfully micromanage the production of tanks and ammunition, it is hard to believe that bureaucrats can pull off the much more difficult job of producing the most effective outcomes for individual health.

Third, like the misbegotten initial stages of World War II mobilization, Obamacare is founded on an ideology that runs counter to the fundamental principles of American exceptionalism. The New Deal and the early World War II experience had their intellectual origins in the progressive movement. Championed by Woodrow Wilson, who as a political scientist studied German theories of the administrative state, progressivism sought to impose order on an unruly economy through central planning and expert management. When such controls were applied to the U.S. economy in the midst of the worst downturn in its history, the effects were lackluster at best.

Obamacare resurrects these methods and this faith in central planning. As in the past, they are sparking irreconcilable conflict with individual choice, civil society, and private markets. Nobel Prize-winning economist F. A. Hayek demonstrated long ago that command-and-control bureaucracy cannot match the efficiency of decentralized markets because of the vast amount of information and processing power needed to allocate resources. In addition, private markets advance core American values. The resistance to Obamacare reflects not just differences between Republicans and Democrats, but a rejection by the American body politic of a foreign governing principle. As World War II showed, government achieves its purposes by harnessing, rather than fighting, American individualism and private initiative.

There is, of course, no direct analogy between producing ships and steel and gas masks for the Pentagon and producing more health insurance options and better health care for Americans. Nevertheless, critics of the Obama administration should take a page from FDR. If the congressional majorities don’t yet exist to repeal the ACA, critics should introduce targeted revisions that advance free-market principles. A supply-side solution for health care should increase the number of productive, innovative options. For the past two decades every major reform effort in health care has focused on managing the demand side of the equation. We’ve had HMOs and managed care, practice guidelines, “pay for performance,” and now Obamacare. As John C. Goodman of the National Center for Policy Analysis points out, each involves “buyers of care telling the providers how to practice medicine” and trying to lower costs by redistributing available care, or even rationing it. In Obamacare, those demands come via the insurers, with death panels—the ultimate rationing—just around the corner.

It’s time to reverse the equation, as Bill Knudsen and his colleagues did in the 1940s. Just as the Army and Navy learned to leave contractors alone to figure out how to design a better plane, build it faster, and at a lower cost, and rewarded them with bigger contracts when they did, so government programs like Medicare and Medicaid should reward doctors and clinics that provide better coverage at lower cost. That would spur them to explore new technologies—say, online diagnosing as a substitute for some costly in-person visits. And it would incentivize private insurers to compete and innovate. Government could help by allowing insurance policies to be bought across state lines and instituting tax credits to encourage people to buy portable insurance on their own instead of through their employers.

One more way the federal government could help would be to make the price of medical services and insurance transparent nationwide. A genuine Blue Book guide to the cost of services not only would allow customers to shop the actual marketplace—instead of the phony “market-place” of the Obama exchanges—but also would give health providers and insurers information about who’s providing services efficiently and who’s not. Every auto repair shop has a price list—and auto insurers love to advertise a lower cost for equal or better coverage in their cutthroat battle for customers. Why aren’t health insurance companies running TV ads with talking reptiles? Obamacare, and the perverse incentives of demand-side government management, guarantee they never will.

Reforms like these would take advantage of the efficiency of decentralized markets, and they would align with American principles of individual freedom and limited government. And to the extent they were inspired by FDR’s war mobilization, we would reap the added satisfaction of finding the cure for one of Washington’s worst policy blunders ever in one more legacy from the Greatest Generation.

Copyright 2014 Weekly Standard LLC. Reprinted with permission.

Photo credit: Library of Congress